Houdini-Fun

Houdini 4D Geometry

High dimensional geometry is a really cool topic to research and mess around with.

I wasted a bunch of time looking into it, so you have to as well!

What is 4D?

What does it mean for something to be 4D? Sounds very fancy. Really it’s just another axis to store numbers along.

- 3D coordinates can be stored as a

vector, meaning 3 numbers along(X, Y, Z)axes. - 4D coordinates can be stored as a

vector4, meaning 4 numbers along(X, Y, Z, W)axes.

In other words, we just need to add a W axis alongside the X, Y, Z axes.

Now we can use 4D coordinates just like 3D coordinates:

vector pos3D = {0, 0, 0}; // (X, Y, Z)

vector4 pos4D = {0, 0, 0, 0}; // (X, Y, Z, W)

Unfortunately Houdini is built from the ground-up to deal with 3D coordinates.

Position, normals and velocity (v@P, v@N, v@v) are hardcoded to work with vectors, meaning (X, Y, Z) coordinates.

There are many ways to get around this. The easiest is adding a float attribute to represent the W axis:

v@P = {0, 0, 0}; // (X, Y, Z)

f@Pw = 0; // (W)

Obviously this isn’t much use by itself. It takes lots of time, research and development to get anything cool.

One example is Matt Ebb’s Slices talk. He translates, rotates, extrudes and slices 4D shapes just like in 3D.

To represent 4D shapes, he used many advanced techniques with tetrahedrons, booleans and winding order correction.

Another example is Houdini X4D, a 4D library built with special relativity in mind.

Luckily there’s an easier way for idiots like me. Signed distance functions! As a bonus, they generalize to any number of dimensions.

4D Signed Distance Functions

An easy way to visualise and mess with 4D shapes is using 4D SDFs.

So what is a SDF? I wrote about them on my Vexember and Houdini SDF pages.

SDFs are nice and easy. They take a position and return the distance to the nearest surface to it.

Here’s an example, the distance to a 3D sphere centered at {0, 0, 0} with a given radius:

float sdSphere(vector p; float radius) {

return length(p) - radius;

}

Let’s break it down:

- The input is a 3D position, meaning

(X, Y, Z). - It uses

length()to get the magnitude, meaning the distance from the position to{0, 0, 0}. - Houdini has

length()in 3D and 4D built-in,sqrt(x*x + y*y + z*z)andsqrt(x*x + y*y + z*z + w*w). - It subtracts the radius so the interior distance of the sphere is negative (hence ‘signed distance’).

So what stops us from using a 4D position instead? Let’s swap vector for vector4:

float sdSphere4D(vector4 p; float radius) {

return length(p) - radius;

}

In one change, we now have the SDF of a 4D sphere!

Keep in mind it’s not this easy for every SDF. For example here’s the SDF of a 3D box derived by Inigo Quilez:

float sdBox(vector p; vector bounds) {

vector q = abs(p) - bounds;

return length(max(q, 0.0)) + min(max(q.x, q.y, q.z), 0.0);

}

This heavily depends on each axis, so for 4D it needs another change to include the W axis:

float sdBox4D(vector4 p; vector4 bounds) {

vector4 q = abs(p) - bounds;

return length(max(q, 0.0)) + min(max(q.x, q.y, q.z, q.w), 0.0);

}

These changes can be complicated and error-prone, so it helps to learn more about SDFs before trying it yourself.

4D slices

Since Houdini and our brains work in 3D space, we can’t directly view 4D geometry.

Instead we have to go with the next best thing, 3D slices! Check out Matt Ebb’s talk on this if you haven’t already.

If you chop through a 3D shape, you get a 2D slice:

Similarly if you chop through a 4D shape, you get a 3D slice:

Rendering a 4D sphere

To render a 3D slice of a 4D SDF, you can follow the same steps as rendering a 3D SDF.

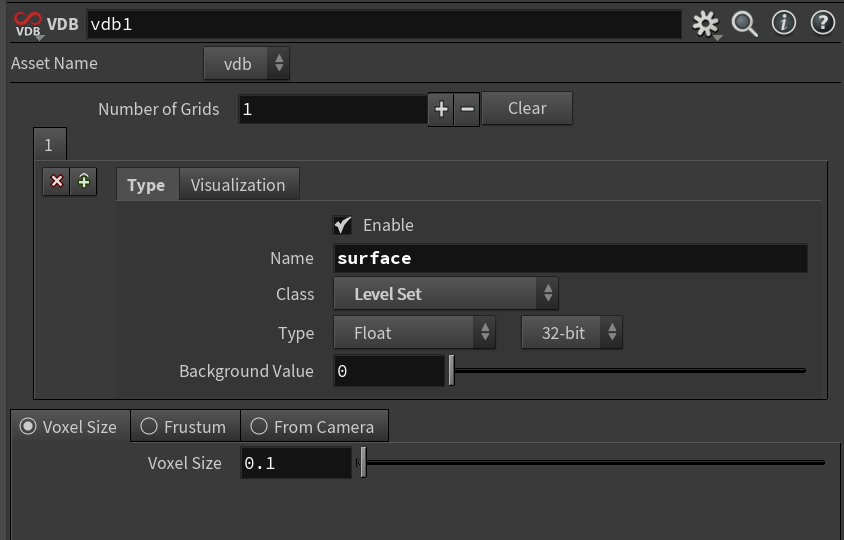

- Add a VDB node. Set the class to ‘Level Set’ and the name to

surface. ‘Voxel Size’ controls the quality:

- Add a VDB Activate node. Set the size of the VDB to anything above 0:

- Add a Volume Wrangle. Here you define your SDF based on

@P, for example our 4D sphere:

// 4D sphere SDF

float sdSphere4D(vector4 p; float radius) {

return length(p) - radius;

}

// W coordinate, this controls the 3D slice we want to render

float w = chf("W");

// Use regular (X, Y, Z) coordinates with our W coordinate to set the slice

vector4 p = set(v@P.x, v@P.y, v@P.z, w);

// Houdini calculates and produces a 3D sphere from the SDF

f@surface = sdSphere4D(p, 1.0);

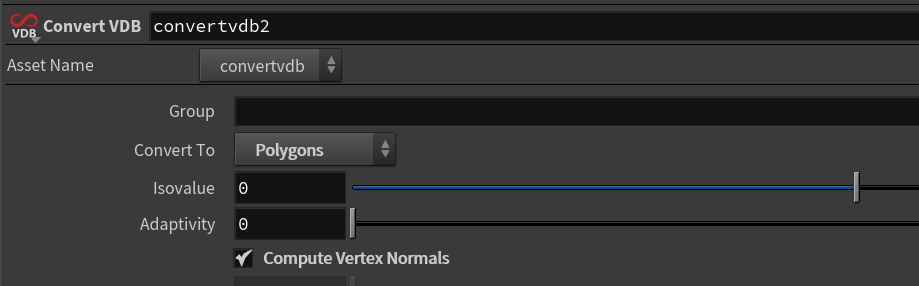

- Add a VDB Convert node set to ‘Polygons’ to convert it from a volume into geometry:

Try messing with the W slider to see what happens. That slider is cutting a 3D slice from our 4D sphere!

| Download the HIP file! | | — |

Rendering a 4D cube

The sphere is pretty boring since it’s a sphere from all perspectives, so let’s try our cube instead:

float sdBox4D(vector4 p; vector4 bounds) {

vector4 q = abs(p) - bounds;

return length(max(q, 0.0)) + min(max(q.x, q.y, q.z, q.w), 0.0);

}

// W coordinate, this controls the 3D slice we want to render

float w = chf("W");

// Use regular (X, Y, Z) coordinates with our W coordinate to set the slice

vector4 p = set(v@P.x, v@P.y, v@P.z, w);

// Houdini calculates and produces a 3D box from the SDF

f@surface = sdBox4D(p, {0.5, 0.5, 0.3, 0.7});

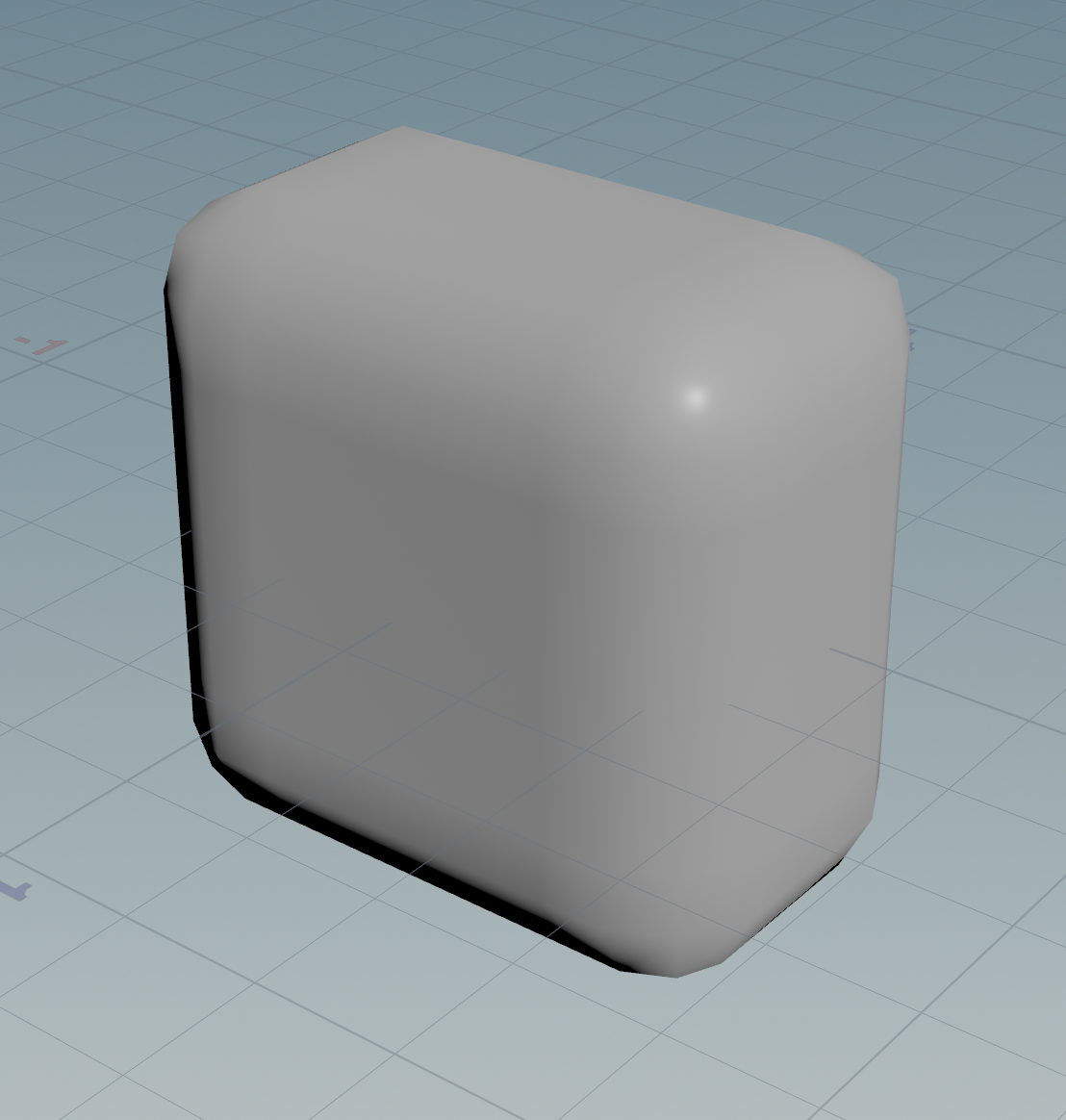

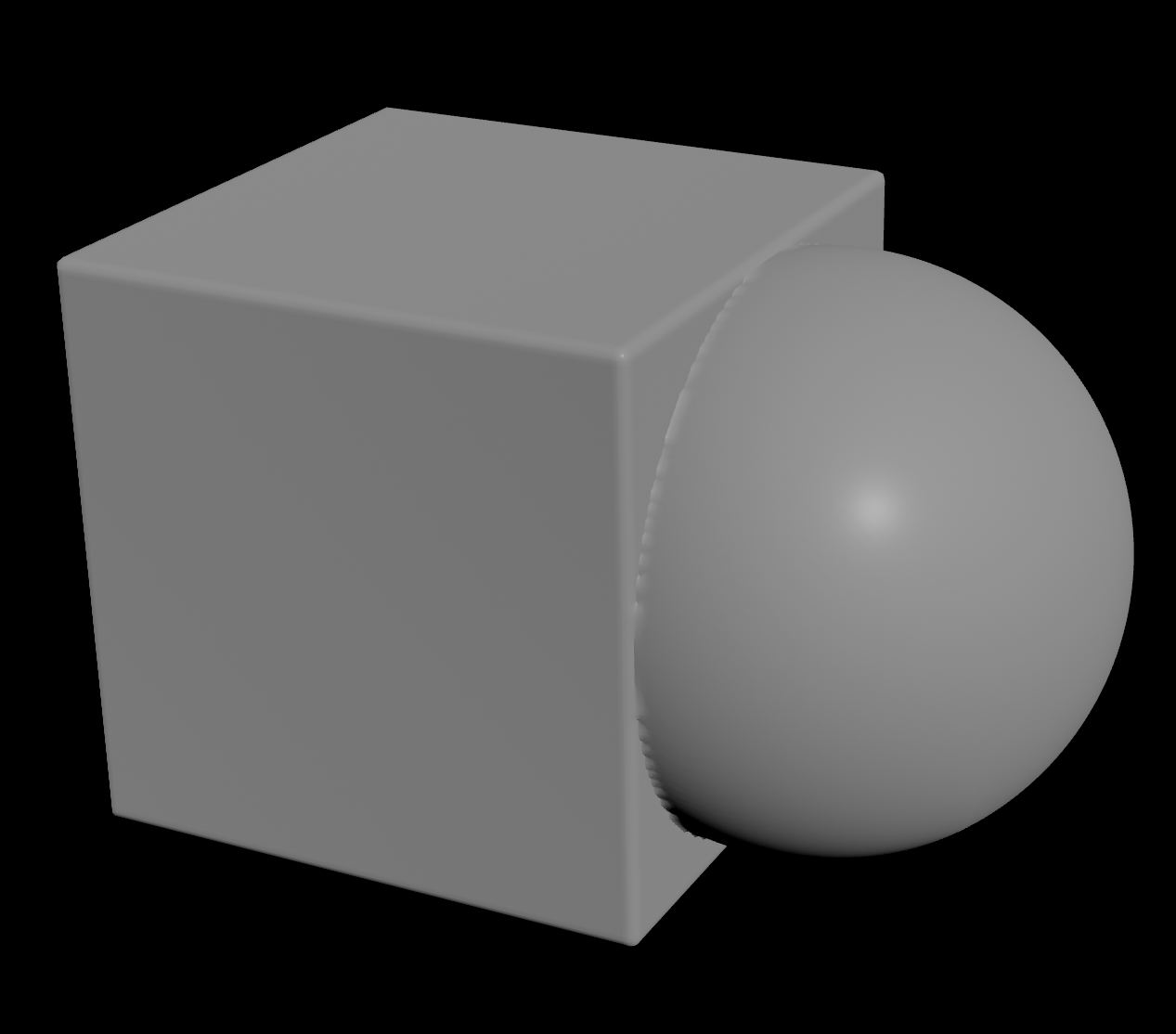

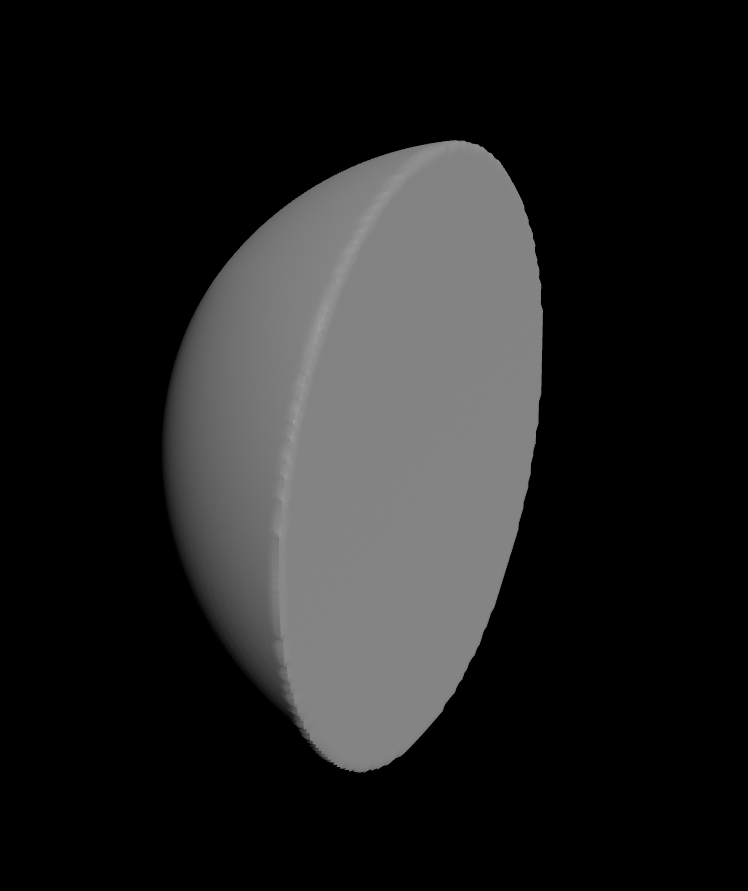

If you run this using the same setup from before, you’ll see a mushy looking shape:

This means your Voxel Size is too large on the VDB node. Use a smaller number like 0.01 to get nice pointy edges:

Now let’s mess with the W slider to see if we can find an interesting slice.

Sadly it’s still pretty boring, the cube just flickers in and out:

To get something more interesting, let’s transform the cube in 4D. First we need to define common transformations.

4D transformations

Translation

Translation in 4D works the same as in 3D. You just need to add or subtract a vector4 from the position:

vector4 p = set(v@P.x, v@P.y, v@P.z, w);

// Translate the cube 2 units to the right on the X axis

p -= {2, 0, 0, 0};

I subtracted 2 units since SDF translations are reversed, because you translate the world instead of the object.

In other words, I moved the world backwards instead of moving the object forwards.

Scale

Scale is also the same as in 3D, but it’s a bit weird when working with SDFs.

Here’s the formula for uniform scale I stole from Inigo:

sdf(p / scale) * scale;

In other words, scale down, sample the SDF, then scale up again:

// Make the sphere 2 times larger

float scale = 2;

// Scale down

float sphereDist = sdSphere(p / scale, 1.0);

// Scale up

f@surface = sphereDist * scale;

This scaling is required so space isn’t bent out of shape. Space should be Euclidean to keep the SDF exact.

If you use a non-uniform scale it distorts the distances, which causes rendering artifacts on ShaderToy.

Note OpenVDB tries to keep SDFs Euclidean, so you might get away with it in Houdini.

Rotation

Rotation is complicated as usual. You have to multiply the position by a rotation matrix, for example:

vector4 p = set(v@P.x, v@P.y, v@P.z, w);

// Rotate around the YW plane over time (angle units are radians)

p *= rotateYW(f@Time);

Here’s a bunch of 4D rotation matrices I stole from a Microsoft article by Steven Hollasch. Multiply the position by any of these:

matrix rotateXY(float theta) {

float c = cos(theta);

float s = sin(theta);

return set(

set(c, s, 0, 0),

set(-s, c, 0, 0),

set(0, 0, 1, 0),

set(0, 0, 0, 1)

);

}

matrix rotateYZ(float theta) {

float c = cos(theta);

float s = sin(theta);

return set(

set(1, 0, 0, 0),

set(0, c, s, 0),

set(0, -s, c, 0),

set(0, 0, 0, 1)

);

}

matrix rotateZX(float theta) {

float c = cos(theta);

float s = sin(theta);

return set(

set(c, 0, -s, 0),

set(0, 1, 0, 0),

set(s, 0, c, 0),

set(0, 0, 0, 1)

);

}

matrix rotateXW(float theta) {

float c = cos(theta);

float s = sin(theta);

return set(

set(c, 0, 0, s),

set(0, 1, 0, 0),

set(0, 0, 1, 0),

set(-s, 0, 0, c)

);

}

matrix rotateYW(float theta) {

float c = cos(theta);

float s = sin(theta);

return set(

set(1, 0, 0, 0),

set(0, c, 0, -s),

set(0, 0, 1, 0),

set(0, s, 0, c)

);

}

matrix rotateZW(float theta) {

float c = cos(theta);

float s = sin(theta);

return set(

set(1, 0, 0, 0),

set(0, 1, 0, 0),

set(0, 0, c, -s),

set(0, 0, s, c)

);

}

Sorry for the huge wall of code, I promise the next section is something interesting.

Something interesting

Now onto rotating our 4D cube.

Take the 4D cube and rotation matrices and paste them at the top of the VEX script.

Now let’s rotate the cube over time. Pick a couple of matrices and combine them with multiplication:

// W coordinate, this controls the 3D slice we want to render

float w = chf("W");

// Use regular (X, Y, Z) coordinates with our W coordinate to set the slice

vector4 p = set(v@P.x, v@P.y, v@P.z, w);

// Rotate the coordinate space so the shape gets rotated too

p *= rotateZX(f@Time) * rotateZW(f@Time) * rotateYW(f@Time);

// Houdini calculates and produces a 3D box from the SDF

f@surface = sdBox4D(p, {0.5, 0.5, 0.3, 0.7});

| Download the HIP file! | | — |

4D normals

So how do normals work in 4D? For 3D shapes you’d use a Normal node, but this gives a 3D normal.

What if we need a true 4D normal representing a true 4D surface? The normal must be 4D too.

We have two options to find the normals of SDFs: smart and brute force.

Smart: Analytical normals

Just like we calculated the distance directly, we can calculate the normals directly. Inigo has plenty of examples.

Directly calculating means we get perfect normals with great performance, since we only sample the SDF once.

However, we need to generalize all the gradient functions to 4D. I’m lazy so I went with the second option.

Brute force: Numerical normals

Remember how a SDF gets the distance to the nearest surface? This distance grows and shrinks depending how close we are.

The change in distance tells us the direction away from the surface, which is the normal of the surface.

To find the change in distance, you can sample the SDF at a few points. You need at least 2 samples per axis, forming a cute little octahedron.

Next you can use the central difference to find the gradient, just like the Trail node in Houdini:

// Use a small distance between samples for best accuracy

float eps = 0.0001;

vector offset = set(eps, 0, 0, 0);

// Sample two points along the X axis

float sampleA = sdf(p + offset);

float sampleB = sdf(p - offset);

// Central difference, like the Trail node

float dx = (sampleA - sampleB) / (eps * 2);

Repeating this for all 4 axes, you get a 4D version of the SDF normal function:

vector4 calcNormal(vector4 p) {

float eps = 0.0001;

vector4 dx = set(eps, 0, 0, 0);

vector4 dy = set(0, eps, 0, 0);

vector4 dz = set(0, 0, eps, 0);

vector4 dw = set(0, 0, 0, eps);

return normalize(set(

sdf(p+dx)-sdf(p-dx),

sdf(p+dy)-sdf(p-dy),

sdf(p+dz)-sdf(p-dz),

sdf(p+dw)-sdf(p-dw)

));

}

This is much slower than analytical normals since it samples the SDF 8 times instead of just once.

I’m sure it could be done with less samples using the tetrahedron technique, but I haven’t looked into it.

Snapping to 4D surfaces

There’s many ways to snap to 3D surfaces in Houdini, like a Ray node set to ‘Minimum Distance’ or v@P = minpos(1, v@P).

So how do you do it in 4D? Luckily it’s simple, we just need the normal and distance.

Basic snapping

If the SDF is exact, the normal tells the direction to travel and the distance how far. Multiply these together and we hit the surface:

vector4 p = set(v@P.x, v@P.y, v@P.z, w);

// Find the direction and distance to the nearest surface

float dist = sdf(p);

vector4 normal = calcNormal(p);

// Move in that direction by the distance

p -= dist * normal;

Improved snapping

The above method only works if the SDF is perfectly Euclidean, which is often not the case.

For example smooth minimum overestimates the distance, which distorts the SDF.

A more robust apporach is using raymarching to minimize the distance.

vector4 p = set(v@P.x, v@P.y, v@P.z, f@Pw);

// Find the direction to the nearest surface

vector4 normal = calcNormal(p);

// Basic raymarching loop, keep iterations low

int iters = chi("iterations");

for (int i = 0; i < iters; ++i) {

// Move in that direction by the distance, approaches to the surface

float dist = sdf(p);

p -= dist * normal;

// Terminate once we get close enough

if (abs(dist) < 0.001) break;

}

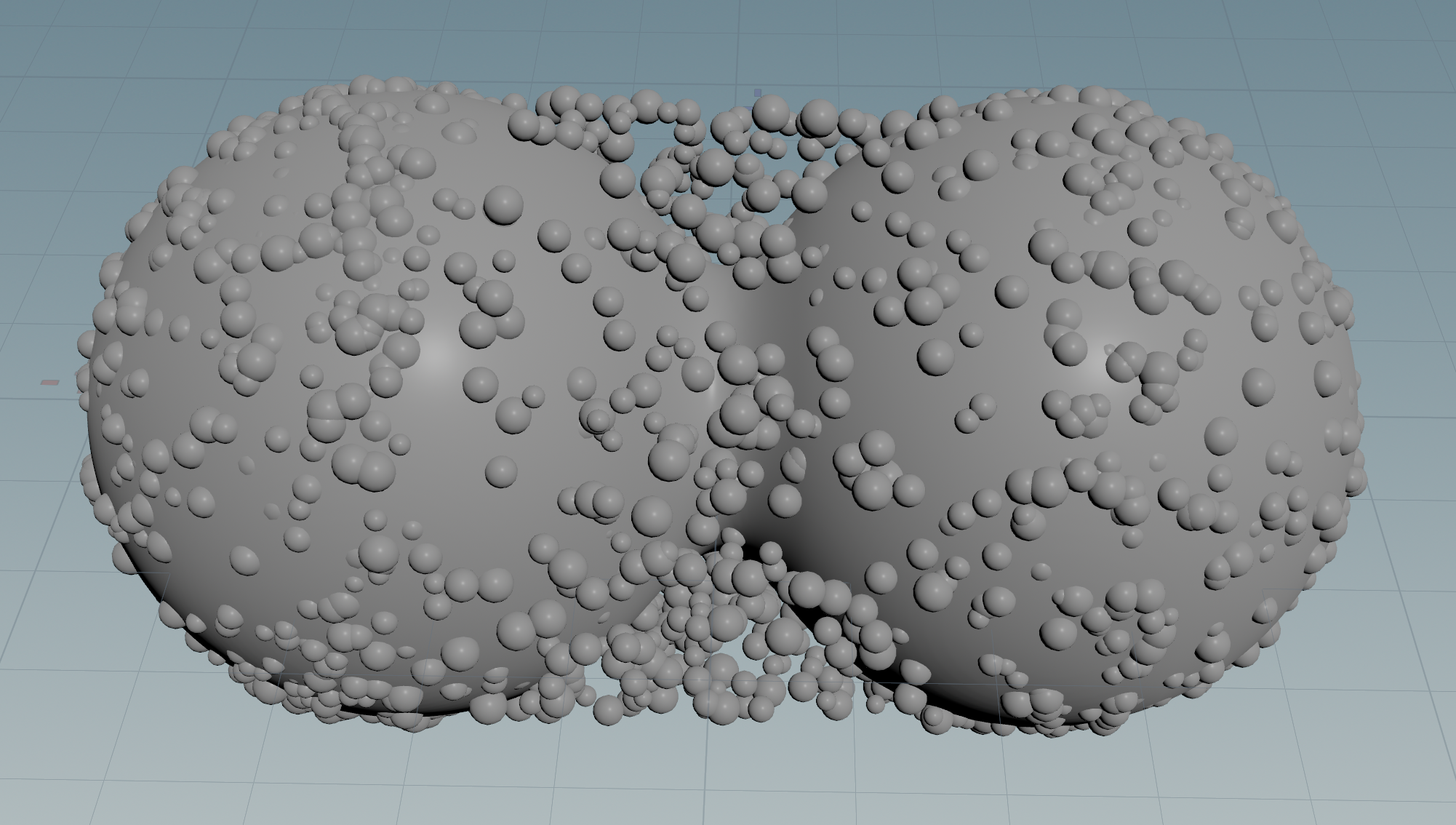

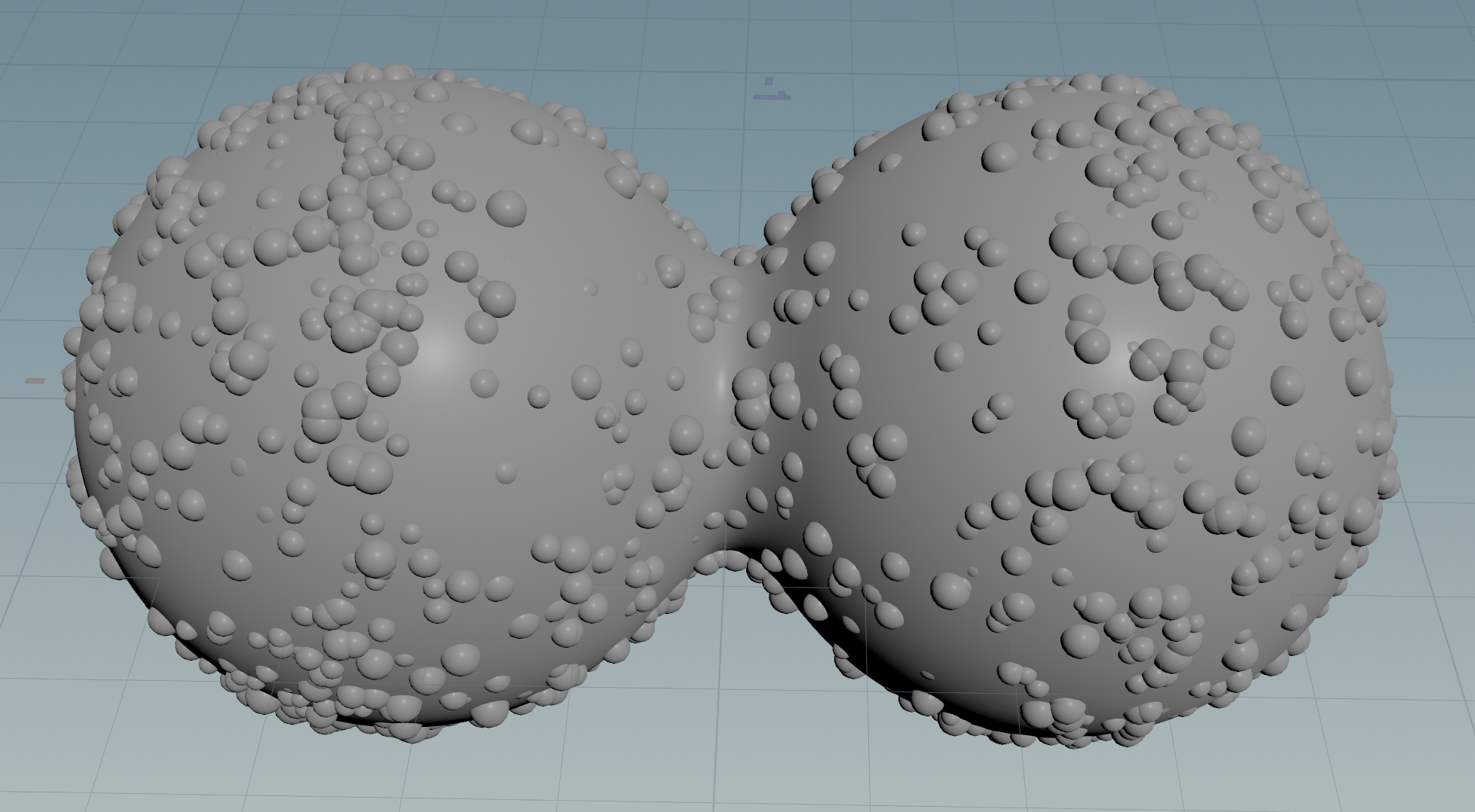

| Basic snapping | Improved snapping |

|---|---|

|

|

| Download the HIP file! | | — |

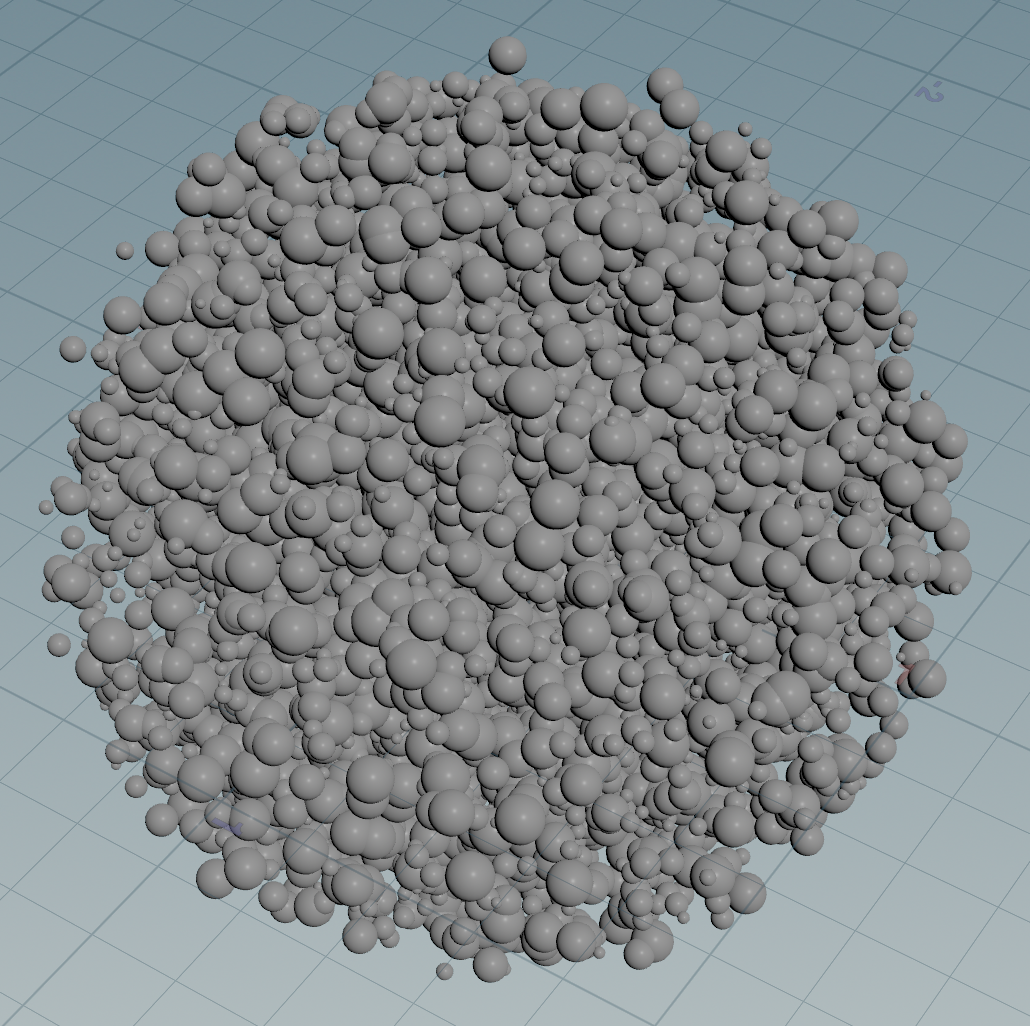

4D scatter

Here’s a simple (but poorly distributed) way to scatter points on a 4D surface.

1. Generate random points

This can be done with built-in nodes like Point Replicate or Points from Volume, but I did it manually.

Since all points generate independently, we can use a wrangle set to ‘Numbers’ so it generates batches in parallel.

I like generating points in a sphere shape. Make sure the radius covers the surface you want to snap to:

// Pick a random 4D position in a centered sphere with a given radius

vector4 randPos = sample_hypersphere_uniform(rand(i@elemnum)) * ch("sphere_radius");

// Add a point with that 3D coordinate

int id = addpoint(0, vector(randPos));

// Add the W coordinate as a point attribute

setpointattrib(0, "Pw", id, randPos.w);

// Randomize pscale for later

float radius = fit01(rand(i@elemnum + 1), 0.03, 0.06);

setpointattrib(0, "pscale", id, radius);

Another option is generating points in a box shape. Make sure the bounds cover the surface you want to snap to:

// Generate a random 4D position between {0, 0, 0, 0} and {1, 1, 1, 1}

vector4 randPos = rand(i@elemnum);

// Optionally fit it to a new bounding box

vector4 fitPos = fit01(randPos, chp("bounds_min"), chp("bounds_max"));

// Add a point with that 3D coordinate

int id = addpoint(0, vector(fitPos));

// Add the W coordinate as a point attribute

setpointattrib(0, "Pw", id, fitPos.w);

// Randomize pscale for later

float radius = fit01(rand(i@elemnum + 1), 0.03, 0.06);

setpointattrib(0, "pscale", id, radius);

2. Snap them to the nearest surface

This snaps to a sphere, but you can use any SDF. For best results, make sure your random points cover the entire SDF!

You’ll find points inside the sphere since it’s generating in 4D, so you’re seeing all slices at once:

float sdSphere4D(vector4 p; float radius) {

return length(p) - radius;

}

float sdf(vector4 p) {

return sdSphere4D(p, 1.0);

}

vector4 calcNormal(vector4 p) {

float eps = 0.0001;

vector4 dx = set(eps, 0, 0, 0);

vector4 dy = set(0, eps, 0, 0);

vector4 dz = set(0, 0, eps, 0);

vector4 dw = set(0, 0, 0, eps);

return normalize(set(

sdf(p+dx)-sdf(p-dx),

sdf(p+dy)-sdf(p-dy),

sdf(p+dz)-sdf(p-dz),

sdf(p+dw)-sdf(p-dw)

));

}

// Snap each point to nearest point on SDF (assuming perfect SDF)

vector4 p = set(v@P.x, v@P.y, v@P.z, f@Pw);

p -= calcNormal(p) * sdf(p);

v@P = vector(p);

f@Pw = p.w;

| Download the HIP file! | | — |

Rendering 4D points

The slowest way to render 4D points is to union them as sphere SDFs.

Starting with the original setup, plug the points into the second input:

Now loop through the points and union them as sphere SDFs:

float sdSphere4D(vector4 p; float radius) {

return length(p) - radius;

}

vector4 worldPos = set(v@P.x, v@P.y, v@P.z, chf("W"));

// Start with a huge distance

f@surface = 9999;

// For each point in 2nd input

int pointCount = npoints(1);

for (int i = 0; i < pointCount; ++i) {

// Read attributes from points

vector p = point(1, "P", i);

float pw = point(1, "Pw", i);

vector4 spherePos = set(p.x, p.y, p.z, pw);

float pscale = point(1, "pscale", i);

// SDF union to combine all spheres

float d = sdSphere4D(worldPos - spherePos, pscale);

f@surface = min(d, f@surface);

}

To make it clearer what’s going on, I’ll union the sphere the points were scattered on.

float sdSphere4D(vector4 p; float radius) {

return length(p) - radius;

}

float sdf(vector4 p) {

return sdSphere4D(p, 1.0);

}

vector4 worldPos = set(v@P.x, v@P.y, v@P.z, chf("W"));

// Start with the 4D surface used for scattering

f@surface = sdf(worldPos);

// For each point in 2nd input

int pointCount = npoints(1);

for (int i = 0; i < pointCount; ++i) {

// Read attributes from points

vector p = point(1, "P", i);

float pw = point(1, "Pw", i);

vector4 spherePos = set(p.x, p.y, p.z, pw);

float pscale = point(1, "pscale", i);

// SDF union to combine all spheres

float d = sdSphere4D(worldPos - spherePos, pscale);

f@surface = min(d, f@surface);

}

The points seem to hover above the surface when viewing 3D slices, but they sit correctly in 4D.

| Download the HIP file! | | — |

4D boolean

You probably saw I used min() to union 4D shapes in the previous code.

This is a common SDF combining operation listed at the bottom of Inigo’s page.

Here’s the rest. Use them with any two SDFs, like a box and sphere:

float d1 = sdSphere4D(p, 1.0);

float d2 = sdBox4D(p, {0.5, 0.5, 0.3, 0.7});

Union

// Union: Merges shapes together

f@surface = min(d1, d2);

Subtraction

// Subtraction: Removes one shape from the other ('SDF Difference' in OpenVDB)

f@surface = max(-d1, d2);

Intersection

// Intersection: Isolates overlapping regions of both shapes

f@surface = max(d1, d2);

Exclusive Or

// Xor: Isolates regions where the sign mismatches (e.g. positive and negative)

f@surface = max(min(d1, d2), -max(d1, d2));

Keep in mind most of these screw up either the interior or exterior distance.

As mentioned OpenVDB tries to fix this. If it fails, just use VDB Combine in 3D.

| Download the HIP file! | | — |

Storing dead bodies on the W axis

Since the W axis is pretty hard to explore, it’s a great place to store your deepest darkest secrets.

Let’s use it to frankenstein two 3D SDFs into one horribly broken 4D SDF!

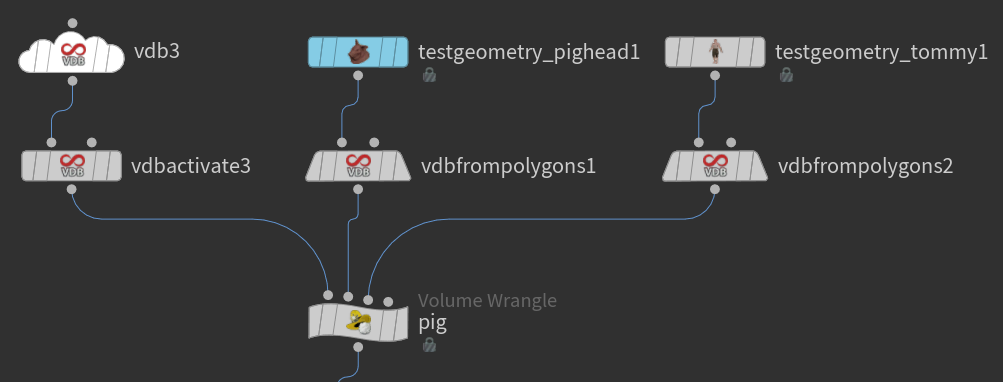

- Take any 2 bits of geometry and use VDB from Polygons to convert them into distance VDBs. I chose the pig and tommy:

- Mangle them into 4D space by sampling their distances along random axes:

// Set W to the Z axis, just in case things weren't broken enough already

vector4 pos = set(v@P.x, v@P.y, v@P.z, v@P.z);

// Rotate around to see the horrors

pos *= rotateZW(ch("Z")) * rotateYW(ch("Y")) * rotateXW(ch("X"));

// Sample (X, Y, Z) for the pig's distance

float pigDist = volumesample(1, "surface", set(pos.x, pos.y, pos.z));

// Sample (X, Y, W) for tommy's distance

float tommyDist = volumesample(2, "surface", set(pos.x, pos.y, pos.w));

// SDF union to combine the distances into one horrible non-Euclidean distance

f@surface = min(pigDist, tommyDist);

By rotating the shape in 4D, we can observe the horrors as tommy and the pig try to escape their reality.

| Download the HIP file! | | — |